At first, I didn’t realize that the stuffed animals had a monstrous quality. It took me a while to see it. When I first started buying craft objects it was because they were, obviously, gifts. I was interested in gift-giving. Artists were going on about this in the art world at the time-the artwork, as gift, was supposed to be an escape from the commodification of art. So I began buying things that I recognized were made by hand. My assumption was that they were meant to be given away-most craft objects are generally made, specifically, to be gifts. The handmade objects I found in thrift stores were, most likely, not sold. I started hoarding them; I had never really looked at dolls or stuffed animals closely before. I became interested in their style-the proportions of them, their features. That’s when I realized that they were monstrosities. But people are not programmed to recognize that fact-they just see them as generically human. Such objects have signifiers of cuteness-big eyes, big heads, baby proportions. You can empathize with those aspects of them. But when I blew them up to human scale in paintings they were not so cute anymore; if you saw something like that walking down the street, you’d go in the other direction. I became interested in toys as sculpture. But it’s almost impossible to present them that way, because everybody experiences them symbolically. That’s what led to my interest in repressed memory syndrome and the fear of child abuse. This wasn’t my idea-I was informed by my viewers that this is what my works were about. I learn a lot from what my audience tells me about what I do.

From Glenn O’Brien, “Mike Kelley” Interview (2008)

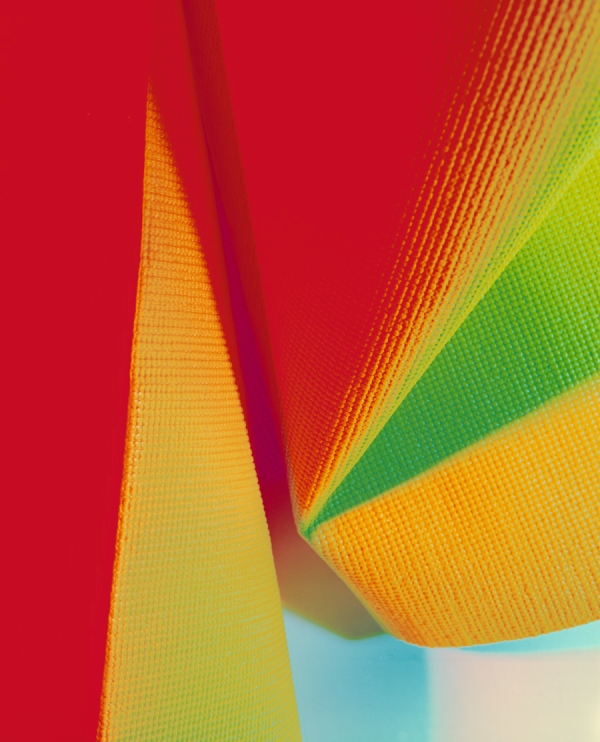

EILEEN QUINLAN

EILEEN QUINLAN (American, b. 1972)

Read this introduction to the work and person of Eileen Quinlan by Steel Stillman (Art in America, 8 March 2011)

– and –

this review by Maika Pollack of the New Photography 2013 show at the Museum of Modrern Art, in which Quinlan’s work is discussed (Gallerist NY, September 24, 2013).

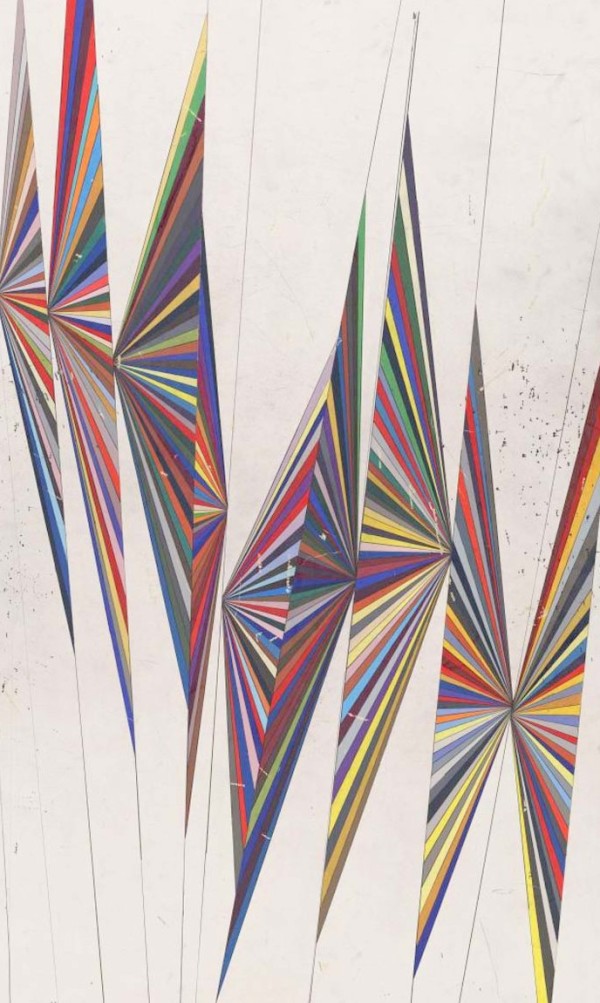

MARK GROTJAHN: Butterfly Paintings and Drawings

The so-called Butterfly paintings and drawings of Mark Grotjahn (American, b. 1968) combine analytical hard-edged abstraction and one-point perspective to make 2D images appear as 3D objects. This type of abstraction is the means by which the perspective system reveals itself—and vice versa. They consist of two distinct phenomenological and theoretical universes that neither cancel each other out, nor represent anything. With two means and no ends, one would expect a more ascetic, conceptual type of image, but Grotjahn’s paintings are lavishly decorative and unabashedly entertaining. This lack of anxiety about the picture plane, flatness, figuration and illusionism is the clearest sign that the modernist endgame has either ended or come full circle.

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN: Recent Portraits of Elizabeth II

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN: Recent Portraits of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II, the queen regnant, is the most-portrayed individual in history, with some 819 official portraits logged since her birth in 1926. Some have been spectacular successes, like Pietro Annigoni’s portrait of the young queen, wearing the robes of the Order of the Garter, painted for the Worshipful Fishmonger’s Company in 1955 and Cecil Beaton’s glamorous photographs of the 1960s; others have not. The failed images go wrong by employing the conventions of aristocratic portraiture of the 18th and 19th centuries for the representation of 20th- and 21st-century subjects. The old formula, which dates back to Van Dyck and Rigaud, calls for military bearing, an idealized yet expressionless face, an impersonal gaze fixed just above the viewer, and places the subject at a distance, both figuratively and literally, from the viewer. When used to portray modern monarchs, those conventions, along with the academic finish and oil paint medium, which are meant to lend dignity to the image, contribute to the pervasive sense of out-datedness, from which flows irrelevance.

In the past 15 years, the Queen has made a conscious effort to keep her public image current by sitting for portraits by critically-admired contemporary artists who work in the visual idiom of her own era, and not that of Queen Anne. This means more photographic portraits and fewer paintings, and the paintings that are commissioned are mainly executed in acrylics. The tone or overall valence of these portraits is different, because the artist, self-effacing in the old formula, is now as much of a presence as the subject. And she is amenable to the process: Elizabeth II is a skilled photographer herself and has hundreds of hours of modeling experience from sitting for her portraits so she is perhaps the portraitist’s ideal subject.

The license to do as they saw fit resulted in the artists thinking about the monarchy and developing highly individual approaches to recording the image of a ruler for posterity. She allowed Lucian Freud to bring us right up to her face and to frankly portray the signs of old age in a non-sentimental manner and which does not suggest a meretricious sense of familiarity. She has also allowed a note of ironic self-awareness to be registered, as seen in the Queen of Scots portrait by Julian Calder (for which she had to stand in a gnat-ridden bog in full regalia for hours) and she gave a cinematic performance of her various official selves and their wardrobes for Annie Liebovitz.

For Chris Levine’s holographic portrait, Lightness of Being, which doesn’t even refer to the Queen in its title, the artist–who is known for his highly-artificial, stylized photographs of Kate Moss and Barbie–has created a superb, completely up-to-date look for the modern monarch, by styling her with makeup and wardrobe that is coolly chic, but appropriate to her royal dignity. In many portraits from the 1960s through the 1980s, the Queen makes eye-contact with the viewer. This was meant to bridge the distance between monarch and subject, but in the end it creates an annoying sense of fake intimacy neither side believes (remember, in the 18th century it was considered a grave offense to look the Sovereign in the eye). Levine drops that convention, and the distant gaze that preceded it, and instead daringly portrays the queen with closed eyes (during sittings for a holographic image made for a bank note, Levine snapped the source still photo while the Queen closed her eyes to rest them in between takes). This conceit forecloses the fatuous illusion of familiarity proposed by the look-you-in-the-eye genre, bluntly informing us that she is distant, that she is not your familiar, but she also not going to lie to you and pretend otherwise. This is not atavistic; it shows clear thinking about about the nature of the monarch, which makes for memorable images.

We recognize the faces of Henry VIII, Charles V, Phillip IV, Louis XIV, and Napoleon because they have been captured by Holbein, Titian, Vélazquez, Rigaud and David; and we do not not remember what Charles II, Leopold I, Charles X, Franz-Josef I or Edward VII because they were painted by less inventive artists. The Queen, too, clearly knows that in the future, her features and her reign will be remembered insofar as the artworks that represent her are remembered and given her recent choices, it seems likely hers will remain a familiar face in the centuries to come.

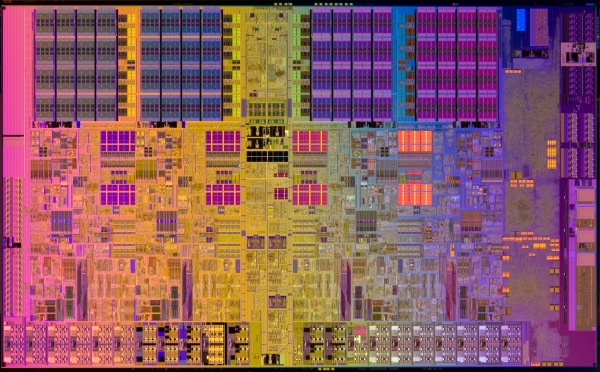

CPU DIE SHOTS

The Aesthetic of the Chip

THE DIE SHOT is the computer industry’s version of the money shot. These gorgeous photographs of a chip’s die, a block of the semi-conducting material of which integrated circuits are composed, are shot under intense light with a high-resolution digital camera using a macro lens or with a combination of microscope and camera. With their geometrical abstract forms and iridescent, jewel-like colors, the die shots look like a psychedelic form of modern art—think Paul Klee on blotter acid. These ravishing images were taken from, several sources, including IC Die Photography and CPU World

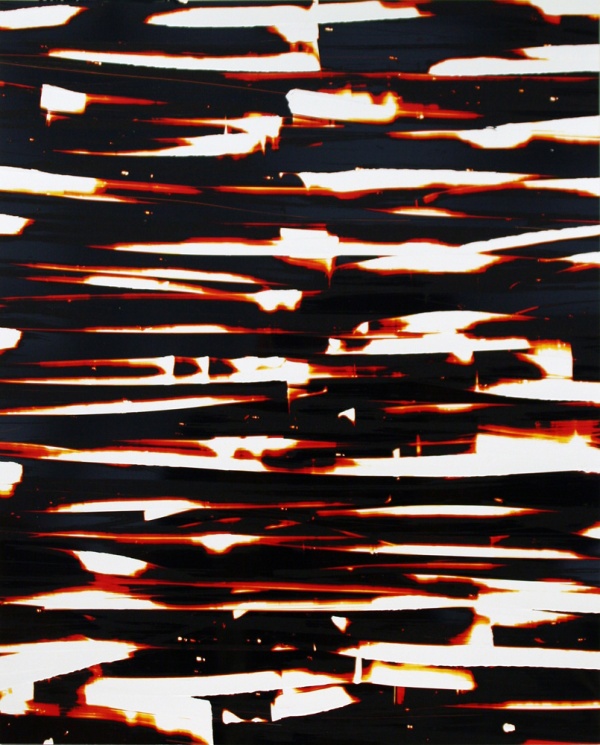

WADE GUYTON: RESUME OR CANCEL PRINTING

Wade Guyton (American, b. 1972) was the subject of a mid-career retrospective, Wade Guyton OS, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in late 2012. The following description of the artist’s work is taken from the museum’s website:

Over the past decade, New York–based artist Wade Guyton (b. 1972) has pioneered a groundbreaking body of work that explores our changing relationships to images and artworks through the use of common digital technologies, such as the desktop computer, scanner, and inkjet printer. Guyton’s purposeful misuse of these tools to make paintings and drawings results in beautiful accidents that relate to daily lives now punctuated by misprinted photos and blurred images on our phone and computer screens.

Guyton’s striking work may been motivated by a printer test sheet or error with an accidentally good-looking image, but they hardly “relate to daily lives now punctuated by misprinted photos and blurred images,” as the press release somewhat sentimentally suggests. For starters, most daily lives do not come equipped with Epson Stylus Pro 9600 inkjet printers, a now obsolete, but surprisingly still expensive, large format machine, used mainly by professional printers. This kind of machine (mal)functions differently than your old HP All-in-One, and requires a considerable level of expertise to wield it for creative purposes. Secondly, Guyton’s pictures are staged errors, deliberately induced, under controlled circumstances. Chance plays a role in his art, but in no way defines it.

Much has been made of Guyton’s use of digital means of reproduction alone, but what that point means to emphasize has nothing to do with analog v. digital media, but the fact that Guyton’s work is conceived and realized entirely mechanically, from computer to scanner to printer, without any actual human mark-making involved. The status and implications of art produced this way have been debated since the 15th century in the context of printmaking and in the wake of Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons, mechanically-generated art should hardly raise eyebrows. This kind of point is not made much in the context of large-format photography, which utilizes similar machinery, because one does not expect a photographer to realize his/her images by hand; in the case of a painter, as Guyton is often styled, the question still comes up.

Painting has been reborn, reconceived, redefined and rebooted many times long after the actual craft of painting ceased to dominate art education and production. Despite its displacement as the pre-eminent medium, the word persists, applied to all manner of two-dimensional media in which pigments are involved, often to highly incongruous effect. The case of Guyton could be imagined as a Magritte painting—a printer connected to a laptop, above which ceci-ci est un pinceau is inscribed. Like carved-stone sculpture, there is a sentimentality about painting—we admire Masaccio and Rembrandt and Chardin and Manet and Picasso and resist the notion that the medium in which they excelled is approaching extinction. Media and image technologies will come and go, but the continuum of image makers is unbroken from the caves at Lascaux to the present moment, so don’t by afraid to call a printer a printer.

FASTER THAN PAINTING: Thomas Struth

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1955) studied painting at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie 1973-77, where he was a student of Gerhard Richter and Hilla and Bernd Becher. His is the highest profile member of a group of German photographers, including Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Jeff Wall, and Thomas Ruff—who work in the medium of monumental color photography using large format cameras and emulsion film. He is currently based in Berlin and New York.

The following quotations were culled from a profile written by Janet Malcomb for The New Yorker in 2011:

On his experience as an entering student at the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie in 1973:

When I came there, it was a shock to realize that I had to regard art as a serious activity and develop a serious artistic practice. Painting and drawing was no longer my hobby, a private activity that I enjoyed. It was something that had categories. Artists were people who took positions and represented certain social and political attitudes. It was an intense experience to realize this. There was very intense judgment by the students—who is doing something interesting and who is an idiot painting lemons as if he were living in the time of Manet and Cézanne.

On painting versus photography:

After I started taking photographs from which I would make my paintings, I realized that the photograph already does it. The photograph already shows what I want to show. So why make a painting that takes me five months to finish and then it looks like a photograph?

On the limitations of the photographic image:

Some of the pictures don’t show what I was thinking. For instance, when I went to Cape Canaveral as a tourist I was struck with the sense of the space program as an instrument of power. When, as a state, you demonstrate that you are able to do that, it contributes to cultural dominance. I hadn’t realized this before. But when I went there to photograph I saw that it is something you cannot put into a photograph.

A note on the source article:

Early on in her profile of Thomas Struth, Janet Malcomb seems to say that because critical response to Struth has been uniformly positive, she will respond negatively on principle. Throughout her article, Malcomb exhibits a very palpable, and inappropriate hostility to Struth, insulting, criticizing and correcting him at every turn. She deplores castigates critics who admire his work; she misinterprets his photographs; makes middle-brow jokes about his work, and ends the article on a note of particular malice by belittling his recent portrait of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip and then raving about a casual snapshot of Struth, the Queen and the Duke taken by Struth’s assistant after the shoot. She ends by reminding Struth that the Queen had not made her opinion of his portrait known, and then implies he is shallow for caring her opinion, when she was the one who brought it up.

The New Yorker profile is not the right venue for mounting revisionist interpretations of an artist’s work, and, based on her comments on artists, photography and critics, Malcomb would not be the best person to mount that revision.

POST/PRE-PHOTOGRAPHY: Marco Breuer

As completely as No Wave destroyed rock music, in or around January 2006, Marco Breuer ended photography as we know it. He did so by reviving various technologies present at its inception, such as cyanotype and gum bichromate, and he did so, fittingly, without benefit of a camera, lenses, film, or negatives. By subjecting photographic paper to processes that ranged from invasive to destructive (The New Yorker referred to his work as “creative violence”), he produced a scarred and damaged contrapositive of the negative that recorded nothing other than the ordeal of its making.

Breuer himself described his project in milder terms, telling an interviewer that he

was attempt[ing] to strip down the photographic process, to remove the distractions of equipment, and to force imagery out of photographic paper itself. I am interested in the intersection of photography and drawing: the negotiation of the illusionistic space of photography versus the concrete space of the physical mark.

The distractions of the photographic apparatus having been eliminated, do the resulting objects constitute photography or the appropriation of the wreckage of one medium by a newly-minted one? Can the process of deconstructing photography produce photography? If it is photography that remains, at what register of cognition or in which conceptual framework does it intersect with drawing?