Robert Mapplethorpe was the subject of two retrospectives in the last year of his life, Robert Mapplethorpe, at the Whitney Museum of American Art (26 July – 23 October 1988) and Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment, organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, which traveled to five other museums in 1989-90.

The religious right successfully pressured the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington to cancel the The Perfect Moment before it opened in 1989 and caused the Cincinnati district attorney to bring criminal obscenity charges against curators of the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in 1990. Right wing politicians made Mapplethorpe and the exhibition the centerpiece of their campaign to discredit and do away with the National Endowment for the Arts, which ultimately failed.

I want everything to be perfect, and of course it isn’t. And that’s a tough place to be because you’re never satisfied.

–Robert Mapplethorpe, 1987

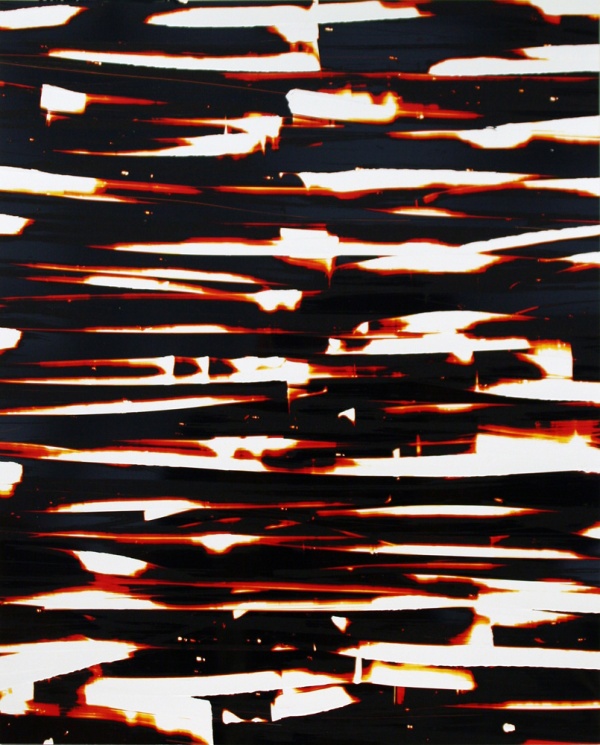

In the starkly-lit, static, black and white photos he produced in the last years of his life, which were heavily featured in the 1988-89 exhibitions, Mapplethorpe certainly aimed at perfection. The still-life arrangements, portraits and heroic nudes are virtually Neo-classical in their purity, restraint, and severity. Every object his camera focuses on turns to stone. In his late portraits in particular, faces are slightly over-lit, like old Hollywood publicity shots, to create a soft focus, luminous effect very close to the lustre of polished marble; applying this technique to actual statuary allows hard surfaces to appear soft and mutable.

I really believe that Robert sought not to destroy order, but to re-order, to re-invent, and to create a new order.

—Patti Smith, 2010

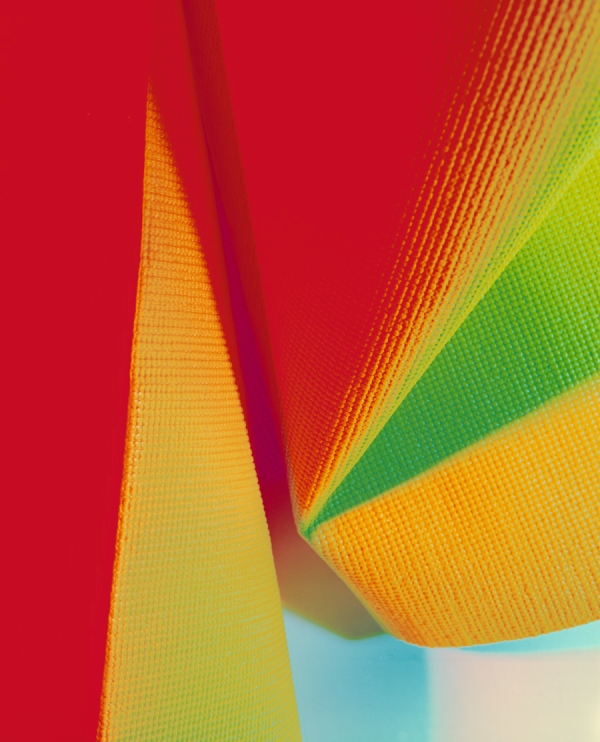

Deeply influenced by Edward Weston and Minor White, Mapplethorpe used the camera to abstract from objects and bodies an inner or underlying essential form. The effect of timelessness—a moment captured and preserved—is, to some extent, unavoidable in photography. When a photographer takes as his or her subject nothing less than beauty itself and purity of form, time ceases to be a referent at all.

In the 1980s, critics praised Mapplethorpe either for his transgressive depiction of graphic and hitherto unrepresentable content or his formalism, which gave the impression of a seemingly split artistic personality (the essays in the Whitney catalogue read as if they were about completely different artists). The problematics of foregrounding the formalist over the hardcore Mapplethorpe became very evident in the expert testimony in the Cincinnati trial, which attempted to explain one version of Mapplethorpe in terms of the other.

Because his Black Book photos are now widely-known, and due to changing perceptions of gay sexuality, Mapplethorpe’s work is less shocking than he was in 1989 (which is what it sought to achieve, on some level). This makes the consistency of his visual interests clearer. The perfect moment turns out to be the perfect form, which is visible in all subjects once the filters of the dominant paradigm are removed.

This concludes The Art of the 1980s series.